In Rock Climbing Part 1, we reviewed the literature to better understand common climbing injuries and risk factors. In this part, we will learn about common climbing moves, and what is required for your body to safely perform them.

The climbing techniques we will discuss are: The Crimp, The Jam, The Gaston, The Lock Off, The Heel Hook, The Back Step, The Drop Knee, The High Step, The Layback, The Stem, and The Undercling. Each technique will include a description of the move and the physical requirements to perform each move.

The Crimp

The crimp grip requires PIP flexion and distal interphalangeal joint extension (Cole, et al. 2020). The crimp places high forces on the annual pulleys and requires strength of the finger flexors (flexor digitorum profundus (FDP) and flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS)).1

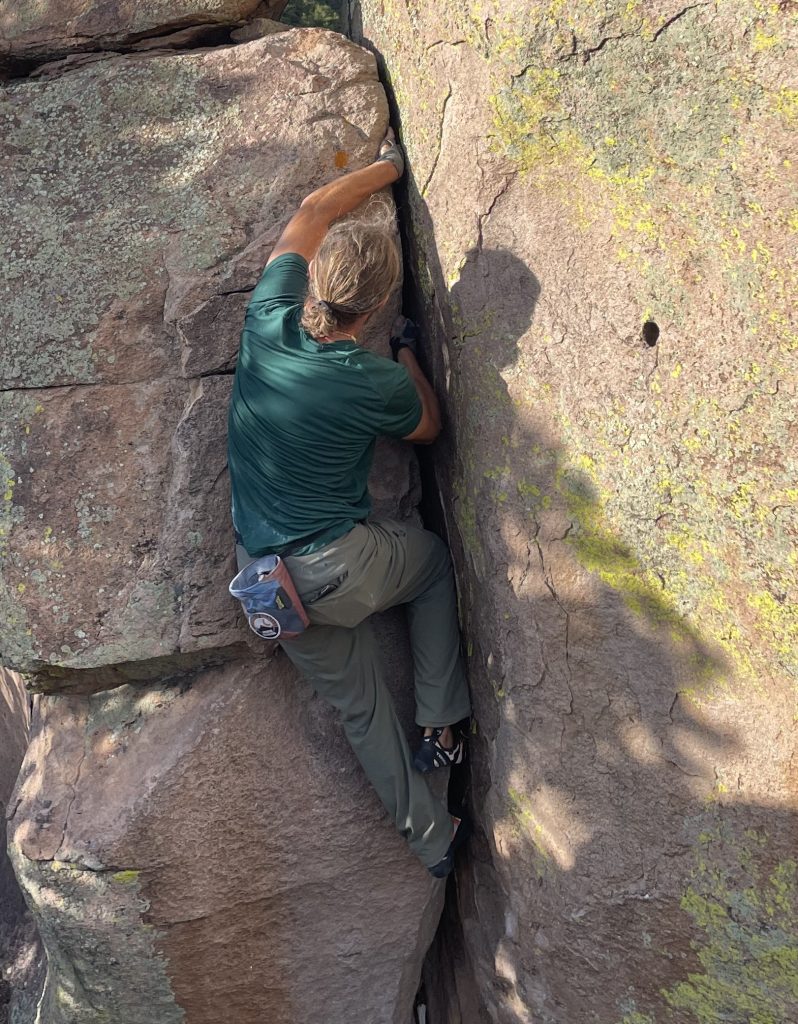

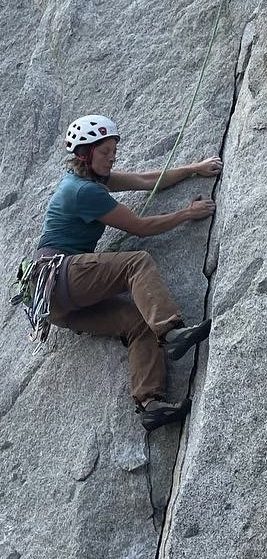

The Jam

The jam involves inserting a hand, foot, or limb into a crack and using friction or torque to hold the position. Foot jams require hip external rotation and ankle inversion and dorsiflexion range of motion. Hand jams involve shoulder rotation range of motion and wrist stability.

The Gaston

The gaston utilizes a pushing action against the hold, which requires shoulder internal rotation and forearm pronation.

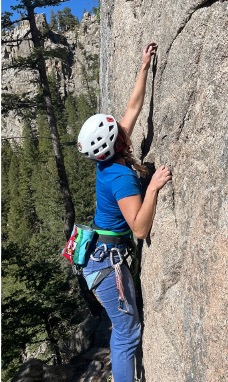

The Lock Off

The lock off position is bending the elbow and holding it to pull oneself up and while reaching for the next hold with the free hand. This requires a strong biceps brachii muscle as well as strong shoulder and fingers.

The Heel Hook

A heel hook consists of pressing the heel onto a hold to transfer weight off the arms, either for balance or to move upward. This requires hip flexion and external rotation mobility, and knee flexion (hamstring) strength. This move can cause a varus (outward) stress on the knee.

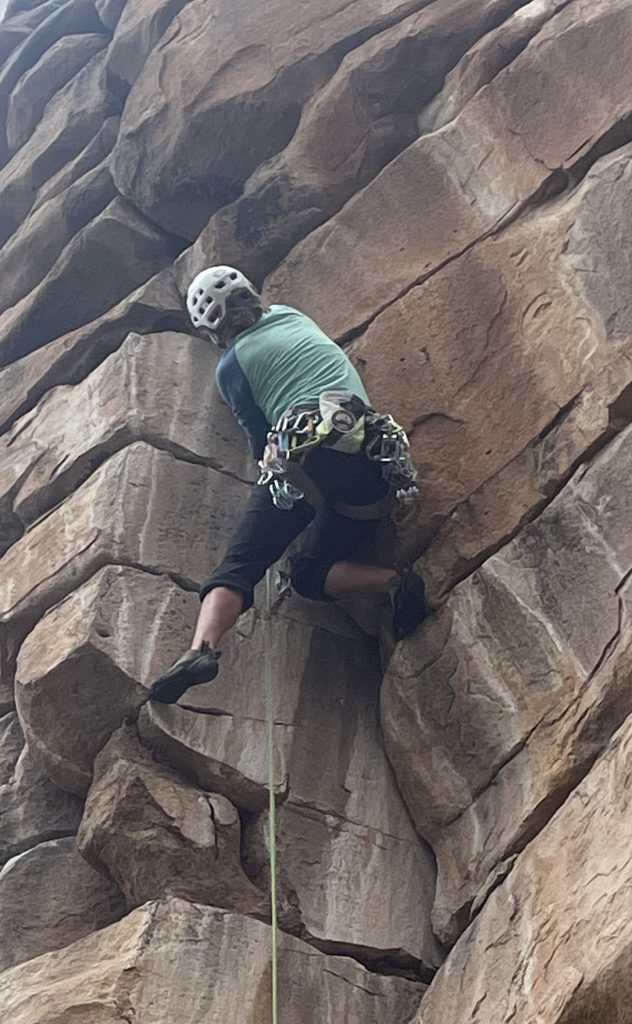

The Back Step

The back step requires turning the body so the outside of your hip is facing the rock, and pressing the outside of your foot against a foot hold to shift weight. This requires hip internal rotation, ankle mobility, and balance.

The Drop Knee

A drop knee consists of internally rotating one hip while maintaining the ipsilateral foot on a hold, causing the knee to go into deep flexion. This can cause a valgus (medial) stress on the knee.

The High Step

In a high step, the climber’s weight is almost fully placed on one leg that is lifted onto a hold with the knee fully flexed, similar to a one-legged squat. The ipsilateral hip is abducted, externally rotated, and flexed.

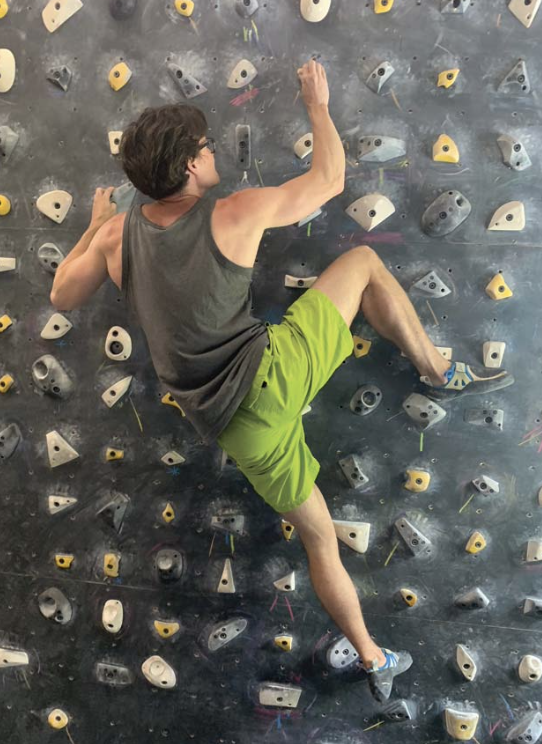

The Layback

For the layback, the climber pulls against an edge or a crack while pushing their feet in opposition. This requires strong grip strength and core tension and can result in stress on the low back.

The Stem

During the stem, the climber uses opposition between two walls or holds by pushing with hands and/or feet. This requires hip and knee flexibility as well as hip adductor and abductor strength.

The Undercling

The undercling is a climbing move where the climber grips a hold with the palms facing upward and pulls while pushing with the feet to maintain balance. This move requires wrist stability, biceps brachii strength, and core strength.

If you are experiencing a rock climbing – related injury, or would like to have assessment of the above techniques, you may benefit from individualized physical therapy in South Boulder with Dr. Sarah Burkhardt.

or email sarah@seatosummitpt.com with any questions!

References:

- Leung, Jonathan MD. A Guide to Indoor Rock Climbing Injuries. Current Sports Medicine Reports 22(2):p 55-60, February 2023. | DOI: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000001036 ↩︎

- Climbing Moves, Holds, & Technique: The Beginner’s Guide. 99Boulders. Published January 12, 2022. [cited 2022 August 7]. Available from: https://www.99boulders.com/climbing-moves-holds-and-technique. ↩︎

- Cole KP, Uhl RL, Rosenbaum AJ. Comprehensive Review of Rock Climbing Injuries. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(12):e501-e509. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-19-00575 ↩︎

(Images from Sarah Burkhardt’s photo collection as well as from https://www.99boulders.com/climbing-moves-holds-and-technique2 and Cole, et al. 2020.3)